The British National Party (BNP) became the most successful political manifestation of British neo-fascism, reaching a peak in 2000 with 50 seats in local government and 2 Members of European Parliament (MEPs). But what is the legacy of this failed attempt at British fascism?

The roots of the BNP can be traced to the economic and social upheavals of the 1970s and 1980s, including deindustrialization, rising unemployment, and the perceived failure of mainstream political parties to deal with working-class grievances. The BNP found fertile ground in areas experiencing rapid demographic changes and economic decline, particularly in parts of northern England and London’s outer boroughs. These regions were often characterized by a white working-class population who felt alienated by multiculturalism and global economic trends.

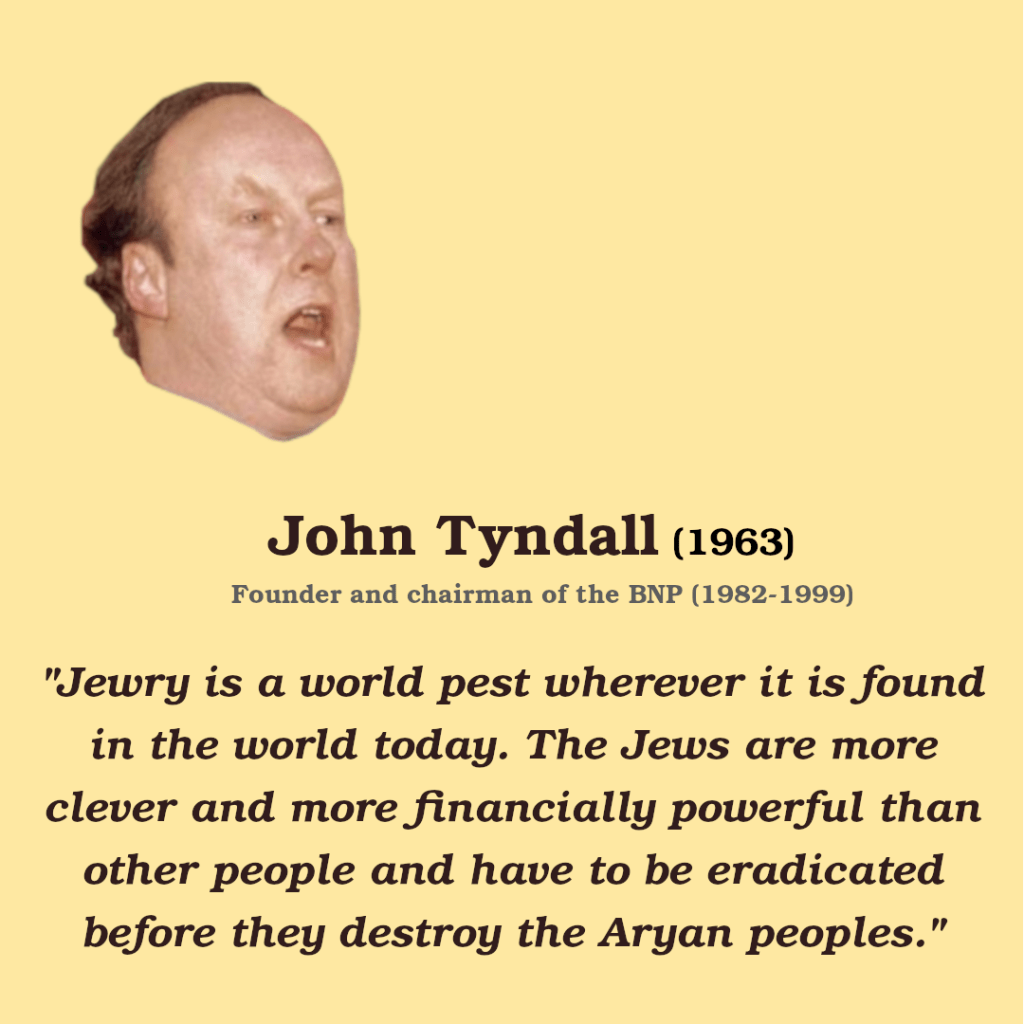

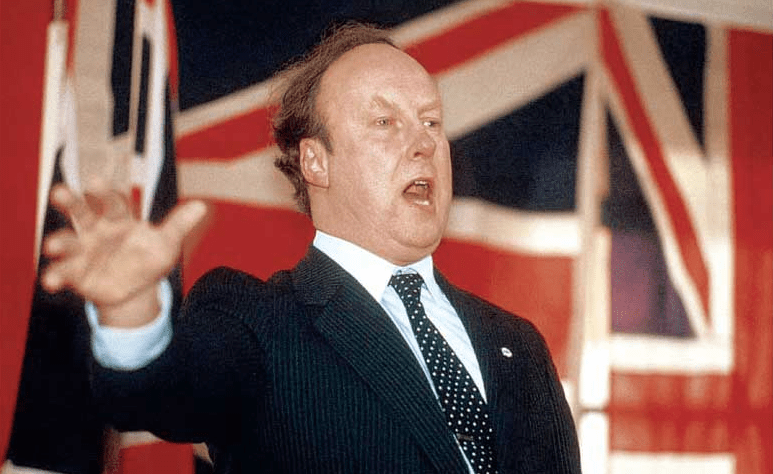

The founder John Tyndall capitalized on these anxieties of change, combining overtly racist rhetoric with populist appeals to nationalism and anti-establishment sentiments. The BNP echoed ideologies used by the Nazis during a similar period of uncertainty in pre-WWII Germany. Central to both movements was the use of a simple scapegoat to explain complex societal issues: a fabricated Jewish conspiracy allegedly working to undermine Western culture and orchestrate a so-called “white genocide.”

However, in these early years, the party struggled to make serious political ground nor shake it’s Nazi image, and so began experimenting with it’s rhetoric.

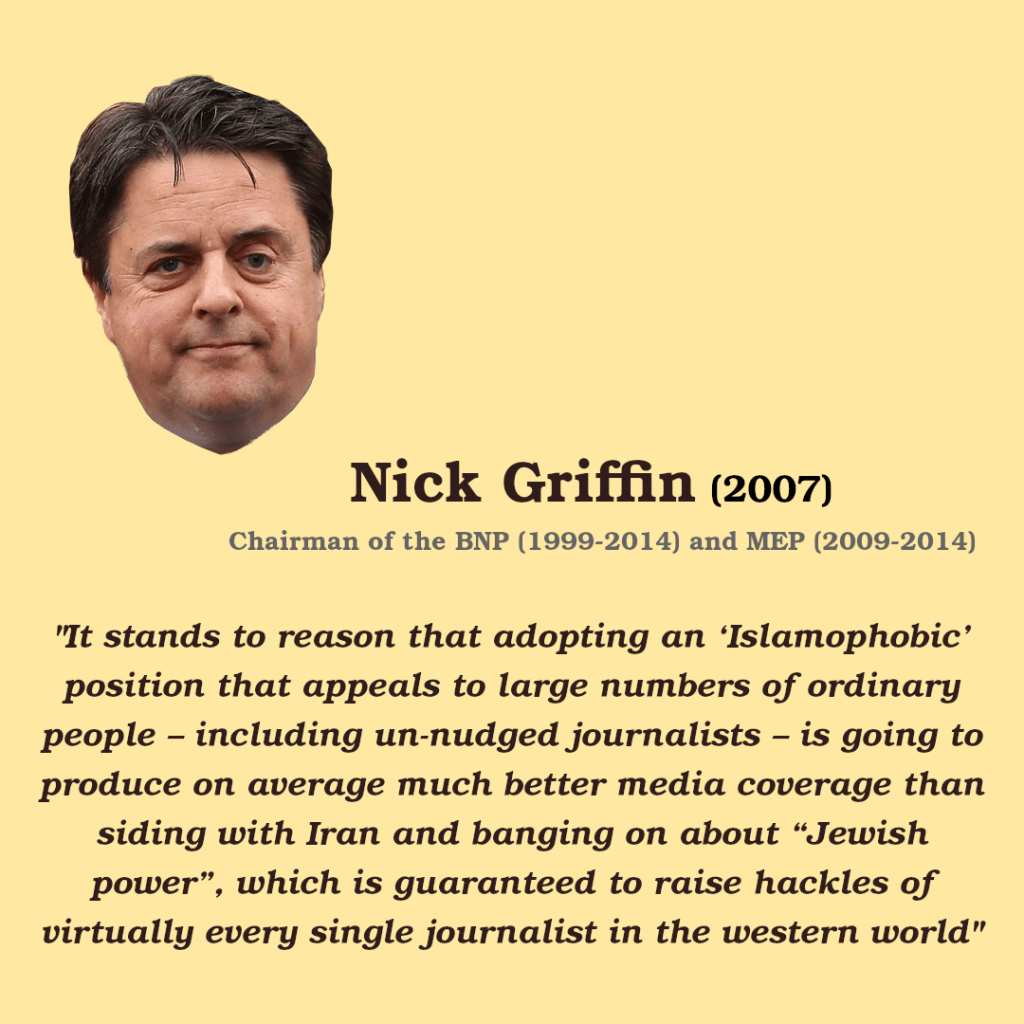

The party experienced a rebranding in the late 1990s under the leadership of Nick Griffin, who sought to broaden its appeal by softening its language and focusing on issues like opposition to immigration, Islamophobia, and Euroscepticism. The group adapted its rhetoric further, replacing references to “race” with “culture” and substituting “Jewish power” with the forces of “globalisation”. Griffin’s strategy aimed to show the BNP as a legitimate voice of white British discontent rather than an extremist fringe group.

White nationalism and racial segregation were not along expressed in their language and policies, but also in the party’s constitution, only allowing membership to “ethnically white” people. However, in 2010, under pressure from legal action brought under the Race Relations Act, the BNP was forced to allow Black and Asian members into their party. Despite this superficial concession to inclusivity, the BNP continued to promote a toxic blend of antisemitic, Islamophobic, and broader xenophobic ideas.

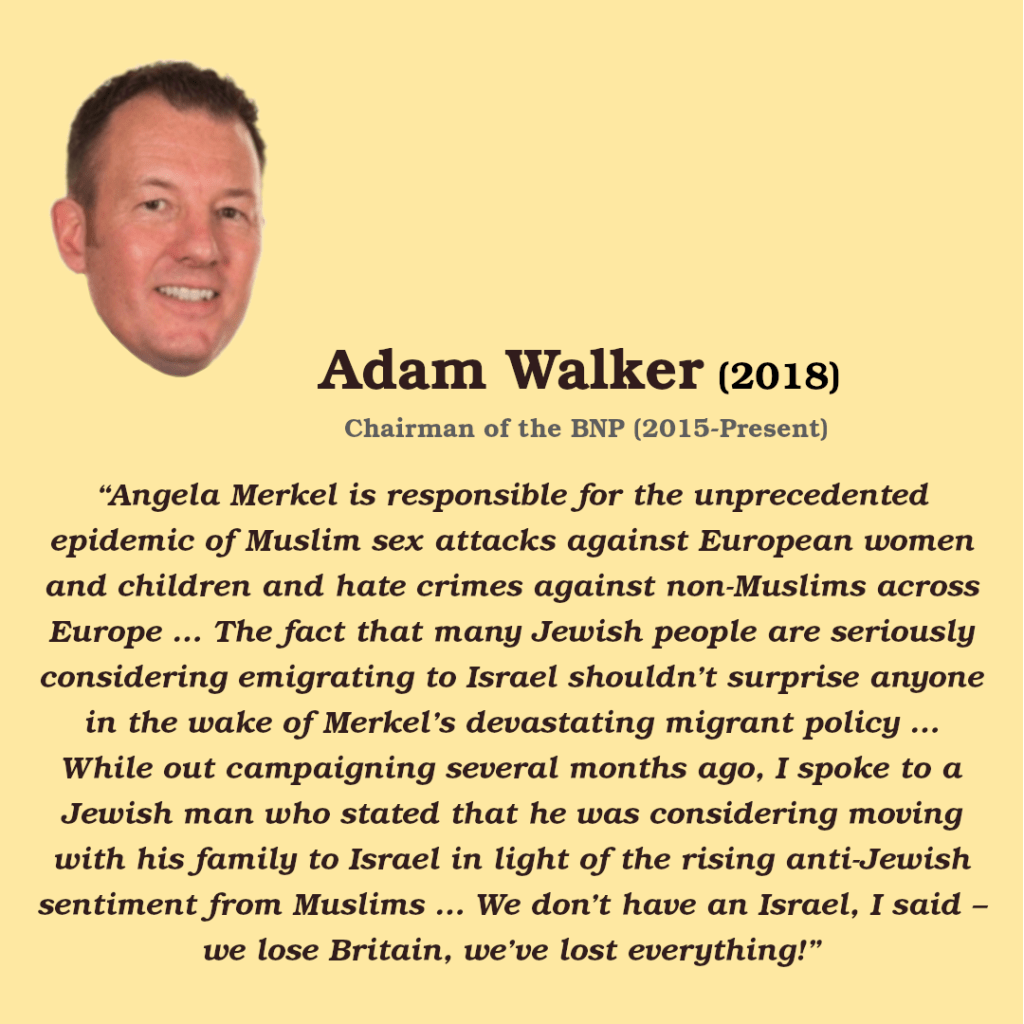

Reflecting broader trends in European far-right politics, Islamophobia became a central focus of the party’s platform, focusing on cultural or religious differences over explicit racial differences. However, the BNP’s inability to convincingly adapt to these shifts, combined with internal divisions and the rise of competing far-right groups like UKIP, contributed to its decline in influence in the years following.

Their current website claims that George Soros, a Jewish philanthropist often vilified by the far-right, is orchestrating the “Islamification of the West” and is regarded as a main figure behind the “Great Replacement” conspiracy theory.

GREAT REPLACEMENT THEORY is a far-right conspiracy theory that claims a deliberate effort is underway to replace white, native-born populations in Western countries with non-white immigrants, often orchestrated by political elites, globalists, Jews or other perceived enemies. The theory alleges that this “replacement” is intentional, aimed at eroding national identity, culture, and power held by white communities.

This ideology has been embraced by many far-right groups worldwide, fueling anti-immigrant rhetoric, Islamophobia, and white nationalist sentiment. Proponents often attribute demographic changes to policies like open immigration, multiculturalism, and declining birth rates among white populations, framing these as existential threats.

The Great Replacement Theory has been directly linked to violent acts, including mass shootings worldwide where perpetrators cited the theory in their manifestos. Despite being widely debunked, it continues to influence mainstream political discourse, particularly through coded language or dog whistles referencing demographic fears, “reverse colonization,” or threats to “Western civilization.”

The BNP’s rise underscores the interplay between economic discontent, cultural anxiety, and political opportunism, revealing how far-right movements can exploit societal divisions during periods of uncertainty. Although politically obsolete today, the legacy of the BNP remains clear. More successful far-right movements, such as UKIP and Reform UK, have carried forward its underlying discourse, reframing the preservation of “British culture” into a more palatable ethno-nationalist narrative.

Sources

Ben Lewis. “The Lost Race (BBC Documentary).” YouTube, 24 Mar. 1999, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z36hh2Q8JLY. Accessed 28 Aug. 2024.

Blumenthal, Max. “Neo-Nazis for Israel?” HuffPost, HuffPost, 9 Feb. 2009, http://www.huffpost.com/entry/neo-nazis-for-israel_b_156497. Accessed 28 Aug. 2024.

Henry Watts. “When Fire-Bombing a Synagogue Is Not a Hate Crime – the British National Party (BNP).” The British National Party (BNP), 17 Jan. 2017, bnp.org.uk/when-fire-bombing-synagogue-not-hate-crime/. Accessed 28 Aug. 2024.

Peter Ashton. “How “Tolerance” Means “Genocide” – the British National Party (BNP).” The British National Party (BNP), 3 Feb. 2017, bnp.org.uk/how-tolerance-means-genocide/. Accessed 28 Aug. 2024.

Verkaik , Robert. “BNP May Have to Admit Black and Asian Members after Court Challenge.” The Independent, 15 Oct. 2009, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/bnp-may-have-to-admit-black-and-asian-members-after-court-challenge-1803635.html. Accessed 28 Aug. 2024.

Leave a comment